Rabbit bubble in Japan

Two Rabbit bubbles in Japan!

The world's first bubble economic event was the "Tulip Bubble(Tulip mania)" in the Netherlands in the first half of the 17th century. A single tulip bulb with a rare pattern was traded for 100000 dollars.

The Japanese asset price bubble of 1986-1991 is the most famous bubble in Japan, but there was another bubble in Japan before that: the "Rabbit bubble" of 1872-1873. In the early Meiji period (1868-1912), when the ban on foreign trade was lifted, imported pet rabbits became popular and their prices skyrocketed.

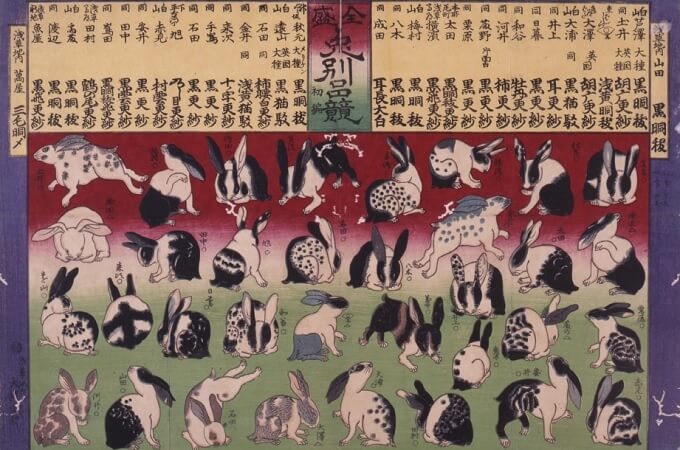

At the time, adopting Western culture was considered a way to improve one's social status. Owning a rabbit became a status symbol like Louis Vuitton or Mercedes-Benz. The number of people who kept rabbits increased rapidly, and rabbit markets were frequently held to buy and sell rabbits. Rabbit fairs were also held, and the prices of rabbits with unusual fur, color, and ear shape soared.

The most popular type of rabbit at the time was the "Sarasa-moyo(Chintz pattern)" rabbit, which had black spots on a white background. A male rabbit with this pattern for breeding was sold for 200 to 300 yen, sometimes 600 yen. There are various theories about the value of one yen at that time, but it is estimated to be 20,000 yen(about 140 dollars) in today's value. The prices of the above rabbits would be 29000 to 43000 dollars or 86000 dollars today. Breeding fees were also 2-3 yen (40,000-60,000 yen, 290-430 dollars) per breeding, so it was possible to get rich if you could obtain a male rabbit with a chintz pattern.

As speculation in rabbits heated up, some people began to sell them under false colors, such as dyeing white rabbits orange. There were also cases of rabbit theft and even murders over the sale of rabbits. In order to calm the bubble, the government decided to introduce a rabbit tax. Owners of rabbits were required to notify the government, and a tax of one yen(about 140 dollars now) per rabbit per month was collected. Some people kept rabbits in secret, but the authorities raided the homes of those who hid them. A snitching system was also introduced and 349 people were interrogated, according to records.

The introduction of the rabbit tax triggered the rabbit bubble that quickly burst. The transaction price of rabbits plummeted in a short period of time to a very low price of 3 sen (600 yen, 4 dollars now) per rabbit. The rabbit bubble, like all asset bubbles, was doomed to burst.

However, the story does not end here. The Dutch tulip bubble never happened again, but the Japanese rabbit bubble did happen again, but in a different form. In 1930-1931, about 50 years after the last rabbit bubble, the Golden Age of Angora occurred over the Angora rabbit.

At that time, Angora rabbit hair was attracting attention in Western countries as an alternative fiber to wool. The technology for producing and processing rabbit hair was beginning to develop. In Japan, too, there was growing interest in the use of Angora rabbit hair. There was an anticipated increase in the demand for Angora rabbit hair, both for export abroad and for domestic industry.

The genesis of the bubble that brought the public into the fold was an article in a magazine. The article stated that rabbits for hair were three to four times more profitable than rabbits for meat and fur. The article emphasized "easy money" to pique people's interest. Japan was in a recession at the time, and the number of people buying Angora rabbits, which were easy and profitable, skyrocketed.

Since only a few companies in Japan were breeding Angora rabbits around 1929, the price of the few Angora rabbits rose. The baby rabbits sold for 40-70 yen, and the parent rabbits for 200-300 yen. Since one yen at that time was about 4,000 yen today, the parent rabbit would cost as much as 800,000 yen(about 5700 dollars) today. However, many people bought them because they thought they would get their money's worth as soon as a baby rabit was born.

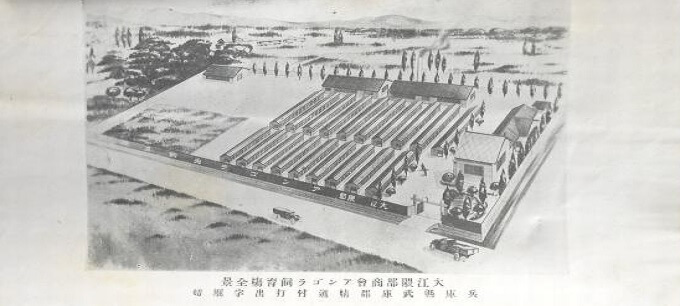

To ride the rabbit bubble, trading companies, laboratories in name only, and rabbit farms were established one after another for the purpose of selling rabbits. By 1930, more than 500 "Angora rabbit shops" had appeared throughout Japan. These shops spurred the price of Angora rabbits to soar. They also advertised in newspapers and magazines that "Angora rabbits are the king of side business" and "You can make money just by shearing rabbits without killing them."

When domestic Angora rabbits were no longer sufficient to meet the demand, Angora rabbit shops began to import rabbits from abroad. The number of malicious Angora rabbit shops increased, with some selling mongrels falsely claiming to be Angora rabbits, others selling rabbits born in Japan claiming to be from abroad, and still others forging pedigrees. Amateurs could not possibly know the authenticity of rabbits, and many people were deceived.

The government received many inquiries, and in the spring of 1931, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry issued the notice. The notice stated, "The processing and commercialization of Angora rabbit hair is still in the research stage, and it is difficult to make a profit from the hair. It is not suitable for farmers, dairy farmers, and the general public to make a business out of it." Since then, newspapers began to publish negative articles about Angora rabbits business in response to the notice.

The impact of the nitice was so great that the price of Angora rabbits dropped instantly. The price, which had been 200 yen in the spring, dropped to 100 yen in July, 50 yen in early August, and by late August there were no buyers even after the price was reduced. Angora rabbits shops went bankrupt one after another, and the second rabbit bubble ended around the fall of 1931.

Nearly 100 years have passed since the last rabbit bubble. Will there really be a third rabbit bubble?

Motorcycle Market

Motorcycle Market Robot Market

Robot Market Digicam Market

Digicam Market Hotel Market

Hotel Market